On Jan. 10, 1956 Magma Copper Company poured their first copper. It was announced later that the price of copper was at its highest level in 90 years at 46 cents per pound. Shortly after, labor unions began organizing and campaigning for the right to represent the workers in negotiations with management. There were 1,675 workers employed at the San Manuel operations. The two major unions involved were United Steel Workers of America and the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, Mine Mill for short. Smaller craft unions had also been formed. In 1956 the San Manuel Copper Corporation and other mines owned by its parent company Magma Copper were the only major mining companies in the United States whose workers were not unionized.

The campaign would get ugly. The Steelworkers charged that the Mine-Mill union was dominated by ”Communists” while Mine-Mill countered that this was nothing more than “red baiting”. It was the time of the Cold War and the era of “McCarthyism” named for Senator Joseph McCarthy who led the anti-communist “witch hunts” from 1950 to 1956. Hundreds of Americans would be jailed, thousands would lose their jobs and many more persecuted for being suspected communists or sympathetic to the communist cause. The main targets were government employees, educators, people in the entertainment industry and unions.

In 1947 the Taft-Hartley Act (Labor Management Relations Act of 1947) became law. It gave the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) the power to spy on Americans including phone tapping of those who were suspected of being communist or associated with communists. It also required that union leaders stay clear of the communist party and that they sign sworn statements that they were not members of the communist party. President Harry Truman vetoed the bill warning that it was a “dangerous intrusion on free speech” and that it will “conflict with important principles of our democratic society”. His veto was overturned.

The law was made to restrict the activities and power of labor unions. It was authored by anti-union congressmen with the support of corporate American capitalists who feared the growing power of labor unions. In 1947 25 percent of American workers belonged to labor unions. When the law was first introduced, labor leaders called it the “slave-labor bill”. It allowed states to enact “Right to Work” laws, prohibited jurisdictional strikes, wildcat strikes, secondary boycotts, mass picketing, closed shops, unions from giving monetary donations to federal political campaigns and radicals from holding leadership positions. Twenty-four states including Arizona have right to work laws. In Arizona it is in the constitution. Taft-Hartley was followed by the Smith Act in 1948 that allowed the government to indict suspected communists and the McCarran Act (Internal Security Act) in 1950 which gave the military the authority to set up internment camps in an emergency to hold non-compliant suspects. The McCarran Act was also vetoed by President Harry Truman who said it “would put the United States Government in the thought control business”. His veto would be overturned. One of the politicians who “specialized” in anti-communism and helped draft earlier legislation that required communists or communist front organizations to register with the federal government and prohibited communists from working in the federal government or obtaining passports was Richard Nixon.

The Second Red Scare as it became known created an atmosphere of fear in the country. The Steel Workers and the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO) saw an opportunity to go after Mine Mill, who they considered a radical union, and absorb some of their members. Throughout their history the Steel Workers and some other unions had attempted to “steal” away Mine Mill members often using communism and even racism, especially in the southern states to divide members. In 1950 the CIO expelled 11 member unions including the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers saying they did not conform to their political standards.

Some of the Mine Mill union leaders were identified as communists. A few resigned but the Mine Mill members stayed loyal to the union much to the surprise of the CIO and Steel Workers. In 1955 the CIO merged with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to form the AFL-CIO. Mine Mill had earned a reputation as a radical and militant union during the early history of their formation.

Mine Mill had grown out of what was once the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). The WFM had been organized during frontier times in the western United States and British Columbia Canada. The WFM was created in 1893. It was formed by the merger of several mine workers’ unions representing copper miners from Butte, Montana, silver and lead miners from Cour d’Alene, Idaho, gold miners from Colorado and hard rock miners from South Dakota and Utah. Many of the miners who organized the union had fought in armed battles with mine owners and government authorities.

In 1892 a bitter struggle between mine workers and mine owners in Cour d’Alene, Idaho took place. Before it was over mine property would be destroyed and people would lose their lives. Hundreds would be arrested and constitutional rights denied. Martial law would be declared and Federal troops would control the area for four months. The Cour d’Alene strike would be the catalyst that formed the union. It was decided to organize the union to counteract the Mine Owner Associations that had been formed to use their money, power and political influence to prevent unions from organizing at their mines.

There would be more pitched battles between WFM members and mine owners, the most notable being the Colorado Labor Wars of 1903-1904. These failed strikes would nearly destroy the WFM depleting them of funds needed to organize and defend union leaders in court trials. The WFM would rename themselves the American Labor Union in 1902. In 1905 they would join with others who advocated industrial unionism and socialism to form a national union federation, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The WFM would leave the IWW in 1907. They would become the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers in 1916.

On Oct. 18, 1956 the election was held with Mine Mill winning the right to represent the mine workers including five other craft unions, the Boilermakers, Electricians, Teamsters, Painters and Railroad Workers. The International association of Machinists elected to not join the coalition and represented themselves. Mine Mill received 600 votes to 479 for the Steel Workers. Seven craft unions 313 votes with 142 “no union” votes while 39 votes were challenged. Of the 1,654 employees eligible to vote, there were 1,573 votes cast.

A group of 86 of 101 workers from the smelter signed and sent petitions to the National Labor Relations Board and letters to their congressmen protesting irregularities in the election and saying they did not want to be associated with the Mine Mill Union. They even sent a telegram to President Eisenhower complaining of pre-election confusion in the balloting process. The telegram stated, “The net result of the confusion was that a communist front union emerged the representative of 1200 workers by a margin of not more than 13 votes and possibly three votes”. The group filed for a charter to form a local Steel Workers Union. The committee members elected to organize the local were William Seeley of Tucson, Riley Smith, Mammoth, Ted Archer, Oracle, Lloyd Boulden, Tucson, Frank Archer, Oracle, Fred Pennington, Oracle and Don Caraway, San Manuel. Charles Wilson of the San Manuel Trailer Park and the temporary president of the group said, “It is the feeling and desire of 86 men of the smelter that we do not want to associate with Mine Mill in any form. We are all good Americans and we want nothing to do with an organization that has such a long reputation of involvement with Communism and which has not cleared itself.”

The protested election delayed the certification of the Mine Mill local. Around the third week of November, 1956, Jack Marcotti who led the organizational drive for Mine Mill in San Manuel was indicted along with 13 other national Mine Mill leaders by a Federal grand jury in Denver, Colo. on charges of conspiracy to defraud the United States government. Marcotti who lived in Tucson denied the charges and said it was not an attack on him personally nor the others listed on the indictment. “It is an attack on the Mine Mill and Smelter Workers Union by the reactionary forces, such as those that can be found in Attorney General Brownwell’s office, among backward employers in the American Mining Congress, and in the raiding Steelworkers union which has been trying unsuccessfully for years to take over Mine Mill’s jurisdiction in the copper mining industry.” Marcotti added “I feel that the only way I could have possibly been accused is through testimony of such a stoolpigeon as the self admitted ex-communist Warren Horrie who was fired by Mine Mill several years ago and has since been working for the Steelworkers union in San Manuel where Mine Mill recently defeated the Steelworkers union in an NLRB election.”

Warren Horie was the international representative for the Steelworkers and had been working in San Manuel helping organize before the NLRB election. He had confessed to being a communist one year earlier and was now fighting them. Jack Marcotti posted a $5,000 bond and was released. He would return to his position as regional director at Mine Mill and begin fighting to get Mine Mill certified and preparing for the first contract negotiations with San Manuel Copper Corporation. The government would drag out the indictments and trial for years. It would become one of a number of mining corporation and Federal government legal attacks against Mine Mill from the 1940s to the 1960s that became known as the “Mine Mill Conspiracy Case”.

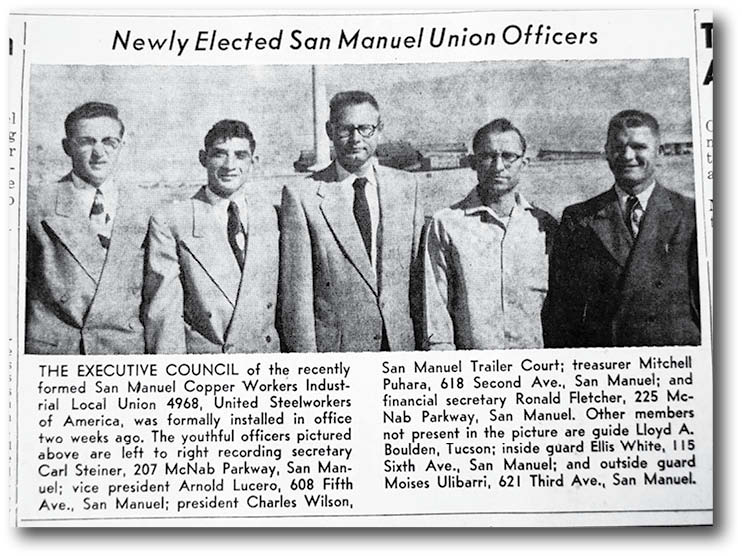

The protesting smelter group would be chartered by the United Steel Workers of America, AFL-CIO and became San Manuel Copper Workers Industrial Local Union 4968, although they had no negotiating authority. Charles Wilson was elected President, Arnold Lucero Vice President and Mitchel Puhara Treasurer. In January, 1957 the Steelworkers dropped their protest amid a report by the National Labor Relations Board that said the four major objections by the Steelworkers were without merit and should be overruled and the “unions which received a majority of the votes cast in the various groups be certified”. A few days later the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers officially chartered Local 937 at San Manuel Copper Corporation. It would pave the way for contract negotiations to begin and for union organizing at Magma in Superior.

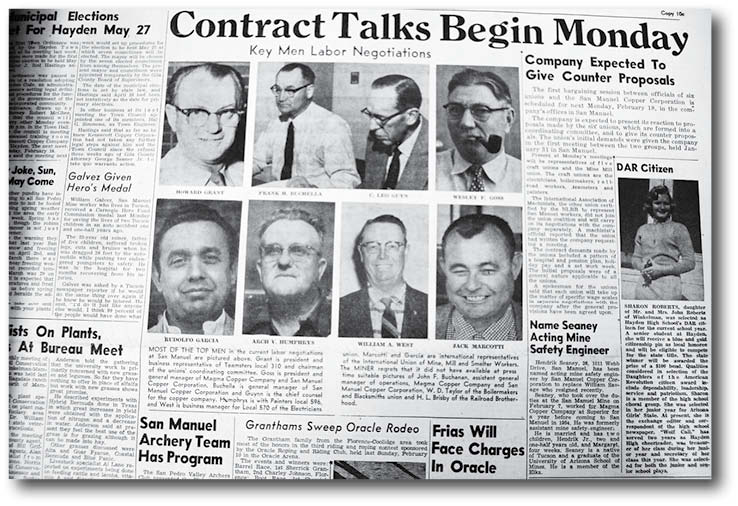

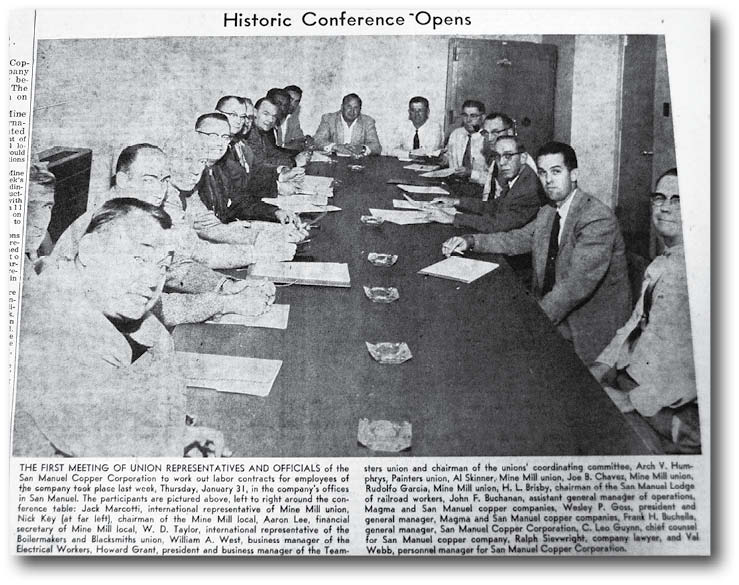

On Jan. 31, 1957 the first union and management negotiations began. The Mine Mill union negotiators were the chairman and financial secretary of the local Nick Key and Aaron Lee. The international representatives were Al Skinner, Joe B. Chavez, Rudolfo Garcia, and Jack Marcotti. Representing the San Manuel Copper Corporation were Frank Buchella, general manager and C. Leo Guyn, the company’s general consul.

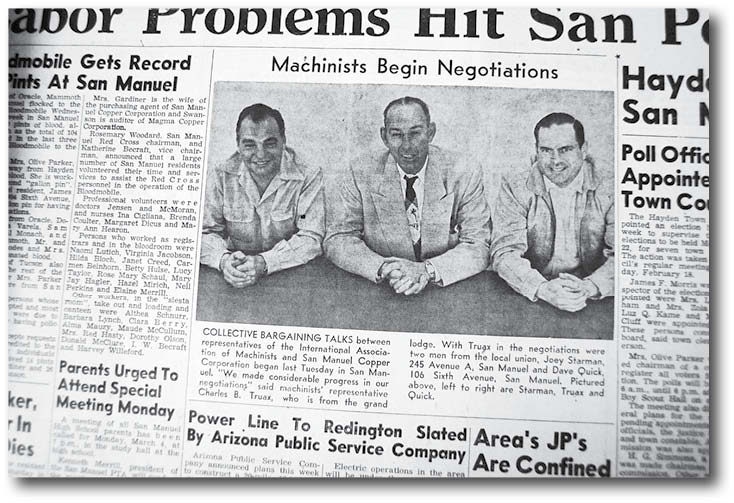

Negotiations went on for 13 weeks. Mine Mill complained that the company was dragging out the negotiations taking to much time to respond to the union’s proposals. President of Mine Mill Nick Key announced that on May 9, 1957 a strike vote would be taken at the Mine Mill office in Mammoth and the Mine Mill Hall on Stone Avenue in Tucson. On May 9, 98 percent of Mine Mill members voted to approve a strike if the company negotiations continued to be delayed. A Federal Mediator W.E. Halloran was called in to oversee negotiations. On the first week of June the contract was settled between the Mine Mill and craft unions coalition. The Machinists Union settlement followed shortly after. No strike was necessary.

After four months of hard negotiating with the San Manuel Copper Corporation, the unions won six cents per hour raise, pension plan, vacation time plus health insurance which included employees in Tucson being allowed to see doctors in Tucson instead of using the San Manuel company hospital. The contract was in line with the national copper industry standards. The contract would last until July 1, 1959 when it would expire. The accusations of communism would continue as did the rivalry between the Steelworkers and Mine Mill and their struggle with the mining companies.

Next: Part II, “The 1959 Strike and more communists in San Manuel”