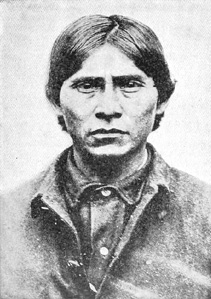

Apache Kid

By John Hernandez

The legend of the Apache Kid is well known among western history buffs. He had once been a trusted army scout and then a convicted killer.

His daring escape on his way to prison left two law men dead and became one of the largest manhunts in Arizona history. The escape became known as the Kelvin Grade Massacre.

The failure of the manhunt to capture the Kid led to his growing legend as killings and raids on ranchers were blamed on the Apache Kid from Globe, down the San Pedro Valley, to New Mexico and south to the Sierra Madre mountain range in Mexico. Rewards were posted for his killing or capture all over the Arizona Territory.

Many men claimed to have killed him, although no one could produce his body. No one ever collected the reward.

Some of the men who claimed to have killed him included the famous Apache scout Mickey Free and lawman Texas John Slaughter. Even the President of the Mormon Church, Joseph Smith announced that a party of men would be attempting to claim the reward.

An article in the New York Times dated November 23, 1900 reported the following:

“President Joseph F. Smith of the Mormon Church, who has arrived here accompanied by O.A. Woodruff and Dr. Seymour, after a tour among the colonies in Mexico, reports the killing of the notorious Apache Kid in the recent Indian raid in Colonia Pacheco.”

“Mr. Woodruff was one of the party that pursued the retreating Indians, and assisted at the burial of the Kid. Among these was one, apparently the leader, who is now positively identified as the notorious Apache Kid. Mr. Woodruff said they will put in an application for the reward offered for him in the United States.”

There are a number of men who claim to have had encounters with the Apache Kid in the Copper Corridor area and lived to tell about it. One man claims to have killed the Kid, another shot the Kid and may have killed him and one met the Kid face to face with rifles pointed towards each other.

The first story is taken from the book “I’ve Killed Men” by Jack Ganzhorn which was published in 1940. His tale of his encounter must be taken with a grain of salt. In fact, probably with the whole salt shaker.

Ganzhorn was a gambler, soldier, and a gunslinger who claims he killed 40 or 42 men. Of these killings, Ganzhorn said, “of course that’s only counting six shooter fights.” His book said he was known as the “world’s fastest man on the draw.” This would probably make him the greatest unknown gunfighter in the history of the west.

He claimed that almost all his killings were in Mexico so many of them were not documented. Trouble is, he waited until the late 1930s to make the claim of killing the Apache Kid and to tell his own life story which is pretty amazing if any of it is true. Ganzhorn was also an actor in silent western movies and a writer of pulp fiction.

Ganzhorn’s claim went something like this:

He says that he learned to shoot a hand gun and the art of the quick draw while working on the 7B ranch near Mammoth around 1897. The ranch was being run by Tom Wills, a well-known rancher, roper and cowboy. Wills would later become the Pinal County Sheriff.

Jack said that a vaquero that worked on the ranch known as Hueco made a leather holster for him. He then got a Colt .44 pistol and would practice shooting and quick drawing for hours.

He said he got so good he could “fan” six quick shots and hit a five gallon oil can with three of the shots from 30 feet. After leaving the ranch Ganzhorn went to Tucson where his father lived.

Around 1901, Jimmy Maish a friend of Ganzhorn’s father had four saddle horses on Jim Neal’s ranch in Oracle. Jimmy had made a deal to trade the horses to a man in Dudleyville. Jack was going to help Jimmy lead the horses to Dudleyville but after arriving in Oracle they found out that two of the horses were being used by Neal’s cowboys and would not be back until the following day.

Maish decided to take two horses himself to Dudleyville. Ganzhorn stayed in Oracle and would bring the other two horses to Dudleyville the next day.

Jack said that Jim Neal told him that instead of taking the road to Mammoth and then going north to Dudleyville, he should head through the Black Hills. He said the trail would bring him out on the San Pedro River near the mouth of the Aravaipa. Ganzhorn decided to take Neal’s advice.

Jack found it to be rough riding through the unfamiliar country. He was still riding as the sun was going down.

He headed into a canyon about 30 feet wide with walls 20 feet high. He had a Marlin .38-55 rifle across his legs when he felt something fly by his head. He then heard two shots.

He glanced up towards the direction of the sound and saw four Indians. Two of them had rifles. Jack spurred his horse to the nearest canyon wall and dismounted. He edged out into the canyon and looked up to see two “squaws” and one man with a rifle on foot. There was another Indian on horseback with a rifle raising it to his shoulder.

Jack aimed and fired. He saw the Indian fall backwards off his pony. The other armed Indian started shooting rapidly at him but Jack had taken cover.

Darkness fell and Jack stayed in his guarded position in the rocks waiting for the sound of the Indians trying to climb down the sides of the canyon wall to get him. He stayed up all night.

When morning came there was no sign of the Apaches. He mounted his horse and rode for a few miles when he came upon the river road. He then ran into a vaquero whose name was Francisco Bojorques.

Jack and Francisco rode back into the canyon to the area where the Indians had shot at Ganzhorn. They found several empty rifle shells and blood on the ground. One blood spot was so large that Ganzhorn’s hat could not cover it all.

Bojorques told Jack that he thought the Indian had been badly wounded and his companions had loaded him back on his horse and taken him away. He also said that it was a good bet that Ganzhorn had tangled with the Apache Kid, his partner Masai and their two “squaws”.

In 1891, an ex-army scout named Dupont had an encounter with the Apache Kid along a trail in the Catalina Mountains. Dupont was carrying a single shot rifle as was the Kid. They faced each other for what seemed an hour or more. Each of them was afraid to fire a shot at each other, knowing that if they missed, they would be at the mercy of the other.

They slowly backed away from each other. The Apache Kid finally saying, “I go now,” as he disappeared down the trail. Dupont headed the other direction toward home.

Ed “Wallapai” Clark was born in Wisconsin. He got his nickname from being the leader of the Hualapai Indian scouts during the Apache Wars. He scouted for General Crook and was well respected among the military and frontiersmen of the time.

Wallapai Clark and the Apache Kid would have a few encounters with each other. Clark had a personal vendetta with the Apache Kid. In 1887, Kid and his band broke away from the reservation after wounding army scout Al Sieber at San Carlos.

While on the run, the band was accused of killing two men. One of these was William Diehl, Clark’s mining partner and friend. Clark swore revenge.

An account of the killing of William Diehl was found in the June 11, 1887 issue of the Arizona Weekly Citizen. The account was from E.A. Clark (Wallapai) as told to a reporter from the Tombstone Prospector newspaper.

On June 3, 1887 around 3p.m., William Diehl and his friend and partner John Scanlon were sitting in their cabin in the Bunker Hill Mining District eating dinner. After finishing supper, Diehl told Scanlon that he was going out about 125 yards from the cabin to cut down a tree.

After a few minutes, Scanlon left the cabin and walked to the shed. He sat down and pulled off his boots so he could trim his toenails. All of a sudden he heard a volley of shots coming from a deep ravine about 15 yards from where Diehl was working.

He looked up to see Diehl fall to the ground. Scanlon rushed into the house and grabbed his rifle. He came out immediately and saw four Indians walking towards Diehl.

Scanlon commenced firing on the Indian closest to Diehl. The Indian ducked and ran behind some trees. The other Indians then began firing at Scanlon who ran back into the cabin. Scanlon returned fire from the doorway.

He fought the Apaches for nearly two hours, only firing when they tried to advance on the cabin as he was running low on ammunition. Another party of Apaches appeared on a knoll about 200 yards from the cabin and called to the Indians engaged in firing at Scanlon. The Indians quit firing and joined the party on the knoll. They then left.

After awhile, Scanlon went to the area where he saw Diehl fall. Diehl was dead, being shot twice in the stomach and once through the heart. Scanlon covered Diehl’s body with a piece of canvas.

He then mounted his horse and rode 20 miles to James Crowley’s ranch on the San Pedro River arriving at two in the morning. At day light, a party of ten men rode from Crowley’s ranch to the scene of the attack. At the time of his death Diehl had been building a corral for James Crowley at a location about 12 miles southeast of the Mammoth Mine.

In 1893, a $5,000 reward was placed by the Arizona Territory for the capture or killing of the Apache Kid. Gold was discovered in the Canada del Oro and the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson.

Wallapai Clark and his partner John Scanlon staked out a claim at Camp Condon 14 miles from Oracle. In February of 1894, Clark and Scanlon left their camp to travel to Tucson for supplies. They left a young Englishman, Jimmy Mercer in charge of the camp.

Clark had heard that the Apache Kid was roaming in the area and warned Mercer to be alert. While Clark and Scanlon were gone, Mercer decided to bathe in a nearby creek. He was naked in the water when the camp dog began barking loudly.

A few seconds later, shots rang out and narrowly missed Mercer who was scrambling out of the creek. Mercer ran swiftly to the cabin and locked himself in while arming himself with a rifle.

Later Mercer found moccasin tracks around the camp and saw that an old pack mare belonging to Wallapai was missing. When Clark and Scanlon returned Mercer told them what happened and showed them the tracks. Clark suspected that it was the Apache Kid who had stolen his horse.

Later in the year, Clark was staying at his cabin in the Galiuro Mountains near Sombrero Butte. He had spotted moccasin tracks around his camp during the day and believed his corrals were being scouted by Apaches. He decided to stand guard during the night near his corrals.

That night, he saw two figures in the darkness approaching his horses. Clark fired at both with his rifle. The first one dropped to the ground after being hit. The second one ran and mounted his horse and fled into the night. Clark was sure he had shot the second one too.

He stood guard during the night and when daylight approached, he saw the body of an Apache woman on the ground. She had been the one Clark had shot first. Wallapai also saw large puddles of blood on the ground where the second Apache had been. He saw more blood on the ground in the direction where the second Indian had fled. Clark believed he had badly wounded the Apache.

Clark rode into Mammoth and alerted authorities. A posse was formed and rode to Clark’s camp and attempted to follow the trail left by the wounded Apache but lost it later that evening.

The military had been notified and sent some soldiers from San Carlos down to the San Pedro. They identified the Apache woman as one that had been riding with the Apache Kid. Many of the local people in the area believed that the Kid had wandered off and found a cave to die in. Others said he had gone to the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico.

Capitan Chiquito, an Apache chief of the Aravaipa Apaches, lived and farmed in the San Pedro Valley at the site where the Camp Grant Massacre took place. The Kid was part of Chiquito’s band and was the son in law of Chief Eskiminzin of the Aravaipa Apaches.

Chiquito said that he believed that the Apache Kid had been seriously wounded by Wallapai Clark but did not die in the San Pedro Valley. He said the Apache Kid made it to the mountains in Sonora where he died from his wounds.

Capitan Chiquito may have been hoping to end the hunt for the Apache Kid in Arizona as Chiquito, Eskiminzin and other Aravaipa Apaches had been forcibly moved by the military to a reservation in Alabama in 1891 where they lived for three years for allegedly helping the Apache Kid. Chiquito was trying to live in peace on his ranch on the Aravaipa.

Then again, he may have been telling the truth, as the Apache Kid was never seen in the San Pedro Valley again.

Alleged sightings of the Apache Kid continued in New Mexico and south of the border in the Sierra Madre Mountains. The Kid was alleged to have been killed in New Mexico by ranchers in the San Mateo Mountains. There is a monument there in what was later named the Apache Kid Wilderness. The monument is allegedly the spot where the Apache Kid was killed. No one produced a body or any evidence that it was the Kid. It was said the corpse was left to rot where it lay and the bones were scattered in the wind.

Wallapai Clark may have summed up the legend of the Apache Kid’s demise when speaking to the press one day about his shooting of the Kid. In October of 1894, Clark was in Tucson and was asked by a reporter from the Weekly Citizen about the Apache Kid.

The newspaper reported: “When asked whether he believed the story that the Kid had gone to the happy hunting grounds, he shrugged his great broad shoulders and said, ‘I’d have to see the cutthroat dead before I would believe that yarn.’”