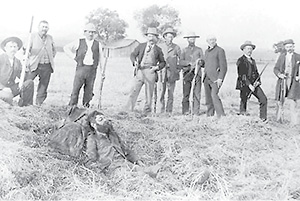

Battle of Stone Corral – Wounded John Sontag in hay. Pictured above him are from left: Samuel Springley, Hi Rapelji, rancher Luke Hal Deputy

Sheriff George Witty, Deputy U.S. Marshal William English, Tom Burns, U.S. Marshal George Gard, reporter Jo P. Carroll, reporter Harry Stuart.

By John Hernandez

Evans’ bullet missed Rapelji. Fred Jackson then stepped around Rapelji and fired his gun. One of the bandits was seen to throw his arms up and fall backwards apparently wounded.

Both sides began firing as rapidly as they could. The bandits retreated behind a pile of hay and manure as it was the only cover nearby. Although it gave Sontag and Evans cover, it did not stop the fusillade of bullets aimed at the haystack.

Both of the train robbers lay on their bellies behind the pile. Sontag had been hit in the arm. Jackson went around to the rear of the house to see if he could get a better shot.

Sontag spotted him and from his position fired his shotgun, hitting Jackson in his left leg between the ankle and knee, shattering the leg bone. Jackson crawled back to the other posse members and told them to keep firing and not to worry about him.

He was taken out of the fight and lay helpless on the floor. The posse members fired another volley into the haystack, this time hitting Sontag in the side. He was in great pain and bleeding badly.

Rapelje and Burns went out of the cabin and attempted to circle around the bandits. Rapelje spotted Evans who appeared to be wounded crawling on his belly away from the haystack. He fired on him and Evans took off running towards the woods.

Rapelje chased him firing as he ran but did not pursue him into the woods as it was now dark. Over 40 shots were reported to have been fired during the shootout which lasted about two hours. As no gunfire came from the haystack, the posse kept watch waiting to shoot at anything that moved.

Rapelje loaded Jackson on a wagon and drove him to Visalia while Burns and Gard watched the hay stack. In the morning, reinforcements had arrived with Rapelji. George Witty, Sam Springley, and Constable William English had rode to the scene as well as E.M. Davidson, a photographer and Jo P. Carroll, a reporter.

The posse spread out and cautiously approached the haystack where they found Sontag buried in the hay with only his face showing. He was helpless and had lost a lot of blood. Evans had escaped although he was badly wounded.

He had taken a bullet in one of his arms and had a bullet scrape his right eye brow that had taken out most of his eye. He walked six miles to a cabin and asked the people for help. He was captured a few days later at the cabin by local lawmen.

Sontag died while in jail from his wounds on July 3. Evan’s arm was amputated and he lost his right eye.

He was tried, convicted and sentenced to life in prison. He would escape from jail, wound an officer and rob another train with an accomplice before being captured again. He then went to prison where he stayed until being paroled in 1911.

He would die in Oregon in 1917 having been banned from living in California. The hunt for and capture of Sontag and Evans was front page news in all of the California newspapers of the time and even made national news. Sontag and Evans became folk heroes.

A popular theatrical play was performed telling their story. Evans’ wife and daughter performed in the play as themselves. Whenever they came out on stage they received a standing ovation from the audience.

A few noted writers wrote stories portraying them as victims of the railroad corporations. Evans denied ever robbing a train and said he only killed in self-defense. As the Dalton gang was also robbing trains in the same area, Sontag and Evans may have been blamed for some of their robberies.

The four men that captured the gang after many larger posses had failed were lauded as heroes. Burns gained notoriety for being a member of the posse that captured Sontag and Evans. He had survived two shootouts with the gang and ridden with Gard, Jackson and Rapelji, who were well known as man hunters and men of “true grit.”

Marshal Gard received the $5,000 reward for the capture of John Sontag and split it with the posse members.

An argument ensued over the reward for the arrest of Evans. Gard, Rapelje, Jackson and Burns said they deserved the reward because they had wounded Evans so badly he couldn’t escape.

Tulare County Undersheriff William Hall, Deputy George Witty and Elijah Perkins said they had captured Evans and therefore deserved the entire reward. The argument became so heated at times that when they saw each other on the streets, threatening words were exchanged.

The story will continue next month. And if you missed Parts 1 and 2, you can find them online at http://tinyurl.com/ctmb5ex. and http://bit.ly/UdYAPT.

The claims wound up in Federal court. In April 1894, an agreement was made and the lawsuit was dismissed. Southern Pacific and Wells Fargo paid Gard $3,000 which he shared, giving Jackson $1,000 and Rapelji and Burns $500 each while keeping $1,000 for himself. Witty, Hall and Perkins divided $2,000.

On September 19, 1894 George Witty filed a civil suit in the Tulare County Superior Court claiming he alone arrested John Sontag and was entitled to the full amount of the $5,000 reward. The case was heard in Los Angeles Court in October 1895.

Burns was one of the witnesses for the defense. After the last day of testimony, while waiting for their train to leave town, Burns and Witty and some of the other witnesses were all drinking in the same saloon.

Witty overheard Burns tell his drinking partners that Witty had impeached himself on the stand. Witty was insulted by the remark and they exchanged heated words. Later as they were boarding the train, another argument broke out between them.

On the train, Witty made some derogatory remarks about Burns and the other defense witnesses. It was deliberately said loud enough for Burns to hear.

Burns rose from his seat and approached Witty who was now standing. They began arguing. As the exchanges became more intense, Witty turned and walked away to the platform outside of the train car.

Burns followed him and as soon as he was outside pulled his gun and shot at Witty narrowly missing him. Witty rushed Burns and they began wrestling for Burn’s gun. Burns fired again striking Witty in the hand. Witty was battling for his life.

As they struggled, they fell over the railing, off of the swiftly moving train. They both landed hard on the ground knocking them unconscious.

When the train arrived at the San Fernando Depot, friends of both Burns and Witty realized they were not on the train. They then caught a train back to Los Angeles.

Along the side of the tracks near Glendale, they spotted Witty lying on the ground alongside the tracks. They had the conductor stop the train and rushed to Witty’s side. Witty was bruised and battered with a gunshot wound to his hand.

He was semi-conscious. He was loaded on the train and taken to Los Angeles where he was hospitalized. Burns, it turns out, was dazed after the fall. When he was able, he walked to Glendale. He had believed that he had killed Witty during the fight and was taken to Los Angeles to turn himself in to authorities.

No charges would be filed against Burns. To add insult to injury, the judgment in Witty’s lawsuit was ruled in favor of the defendants. Witty was ordered to pay $82 in court costs to the defendants.

Burns returned to Arizona where he worked as a bounty hunter and railroad detective. He was also hired to run down cattle rustlers. He once tracked a horse thief from Florence, Arizona to New Mexico. He killed the horse thief and returned to Florence with the stolen horse. Along the border he engaged in a number of shooting scrapes with rustlers and smugglers, the last one occurring around 1899.

While working as a detective in Willcox, Arizona, he was investigating a Southern Pacific train robbery in Cochise County. Burt Alvord, the Constable at Willcox, was a suspect.

Burns was gathering evidence against Alvord and the gang responsible for the robbery. One night, Alvord attempted to kill Burns.

Alvord had heard that Burns was making inquiries about him. One evening he went looking for Burns and ran across him in one of Willcox’s saloons. Alvord had been drinking earlier. When he saw Burns he drew his six gun and aimed at him. Just as he pulled the trigger, a man standing next to him slapped his arm into the air.

The bullet went into the ceiling. Burns quickly reached for his gun but was grabbed by some of the men he had been drinking with.

Alvord had also been wrestled to the ground. Burns and Alvord were separated and later were allowed to go to their respective homes. A short time later, Alvord was arrested for the train robbery along with his co-defendant Bravo Juan.

While in jail, Billy Stiles another law man turned train robber, broke them out of jail. Burns left the area shortly after this and headed north.

Burns punched cows in the Tonto Basin and the San Pedro Valley. In August of 1899 in Pinal County, a housewife accused him of raping her.

The charge was never brought to court. Along the way Burns was gaining a reputation as a “bully.”

He was unpopular among the cowboys of the San Pedro River Valley. In the town of Mammoth, Arizona, Burns had been involved in a shooting incident with a Mexican known as Gaibee.

One story said that Gaibee had been looking for Burns when he entered a saloon and saw Burns behind the bar. Gaibee took off his big sombrero and held it close to his body slowly drawing his pistol and hiding it behind his sombrero.

As Gaibee walked towards the bar, Burns who had already drawn his gun brought it up from behind the bar and shot Gaibee twice. Gaibee would survive the shooting but the incident would turn the local cowboys against Burns.

The cowboys in the area believed a different version of the story where Gaibee had not had his gun drawn and felt Burns had taken unfair advantage of him. From that day on, Burns was not liked in the area.

It did not help that Burns tended to be obnoxious and was known to start trouble especially when drinking.

Although Burns was not liked, he had a reputation as a crack shot and a man not to be trifled with. The cowboys avoided him when they could.

In 1901, Burns was working on the Tom Will’s ranch near Mammoth, Arizona. Burns took a disliking to a young cowhand that also worked at the ranch.

One night they had got into a fistfight at dinner in the bunkhouse which the other cowboys eventually broke up. While out riding Burns would make threats to the young man and on another occasion they exchanged words and a few punches.

On Saturday, June 15, 1901, Burns and the other cowboys were working on an irrigation ditch. Burns and the young cowhand got into an argument over work.

Burns took his shovel and swung it at the cowboy hitting him in the head and cutting his scalp badly. The young cowboy ran to the house with Burns in pursuit. On the way to the ranch house, Burns was intercepted by Tom Wills and was told to pack his things, that he was fired.

Burns retorted, “I will leave as soon as I kill that son of a bitch.” He ran around Wills to the house. In the meantime, the young man had armed himself. When Burns rounded the corner and approached the cowboy, he still had the shovel in his hands.

The young cowboy had a gun and immediately shot Burns twice, the first bullet striking him in the heart, killing him instantly. The man who California newspapers claimed was the “most famous gunfighter in Arizona” at the time was now dead.

The newspapers reported the young cowboy’s name as “Wallace,” then “Willis.” Eastern newspapers called him “Kid” Wallace. The Florence Tribune named him as Miller Wallace.

The Tucson Citizen had a report from a young lady who lived near Mammoth that the name of the man who shot Tom Burns was Willis Miller. The story would make national news.

A coroner’s inquiry was held and Willis Miller was exonerated immediately, the verdict being he had acted in self defense. Tom Will’s influence in testifying for the coroner’s jury may have helped Willis.

Tom was well liked and respected in the area. He would be elected Pinal County Sheriff in 1902. As for Miller, little is known about him following the shooting. Burns body had been turned over to the cowboys at Wills’ ranch.

On the way to the graveyard, Burns’ coffin was in the back of a wagon. The cowboys would mount it like a horse and dig their spurs into the sides of the coffin shouting and cursing Burns.

Some cowboys jumped and danced on the coffin shouting, “We’ll dance him into hell.” One newspaper said of Burns: “He was about 40 years old and a good type of cowboy. He was well known all over Arizona and his fate is regarded as the inevitable result of the life he led.”

Some newspapers said he had 13 notches etched on his pistol. The man who had helped capture California’s most infamous train robbers, survived many shooting scrapes with rustlers and smugglers, and been called “the most famous gunfighter in Arizona” by a California newspaper had messed with the wrong San Pedro Valley cowboy.